The Cottage Linen Weavers

Discover the fascinating history of Ireland's flax farming and linen weaving ancestors.

The Linen Industry in Ireland

People often assume that the linen industry was introduced to Ireland by the English in the 1700s. However, there is a long history of flax being grown, spun and woven into materials in Ireland. You wouldn’t necessarily think now that the textile industry was important to Ireland, but back then much wealth was created through it.

After the 1700s, the exportation of Irish woollens was banned, which was a huge blow to the economy of Ireland. Wool, unlike flax, didn’t need to be imported to Ireland – the sheep were already there. Flax was different in that the seed had to be imported.

After the rebellions of 1688 to 1691, King William III, also known as William of Orange, wanted to help the English economy. He stated:

“I shall do all that in me lies to discourage the woollen manufacture in Ireland, and to encourage the linen manufacture there, and to promote the trade of England.”

Ireland lost its woolen trade completely. Ireland was very suited to the woolen industry. Encouragement of the linen only meant that Irish linen did not have to pay a duty when exported out of Ireland.

Growing Flax

It was the North of Ireland that expanded the growing of flax and the production of linen. Huguenot migrants around 1700 brought knowledge of better manufacturing techniques. Local landlords encouraged the industry. The linen industry initially operated out of the linen triangle – Lisburn, Ballymena and Belfast. Eventually, the spinning of the thread expanded out to the whole of Ulster, north Connacht and north Leinster.

In Ireland, a small area of ground could produce your flax, and keep a family going reasonably well, but there would have been a lot of competition for this land.

Pulling Flax

Flax is a rotation crop which means that you couldn't grow flax in the same field year after year. You grew it you once every 5–10 years. Seeds had to be imported from America, Holland or Russia, and that made it quite expensive.

Flax is a tough crop with fibres right into the root, which is why it was pulled by hand. If you wanted to cut the flax, it would leave too much of the fibre in the ground. Farmers didn’t want to do this because it would waste precious flax fibre.

Growing good flax needed plenty of labour to plant, weed and harvest the plant. Harvesting the crop depended on the type of flax farmers wanted to sell. The flax was pulled 100 days after it was sown, or three to four weeks after the first flowers appeared. Fine linen was pulled earlier, but if it was pulled too soon, the fibres would be too soft and couldn’t be made into linen.

If the flax was twisted or flattened by the rain, it was pulled as soon as possible because once it's flattened by the rain, the flax can be damaged. If it was too sunny, the plant went brown, and the fibres became brittle and discoloured. If this happened, the plant was also pulled quickly.

The Dam

After harvesting, the flax was put into a dam so that the outside of the flax plant rotted. This allowed the farmers to harvest the flax fibres. This was a job that had to be done very carefully so as not to damage the flax.

The flax was layered into the dam and weighed down with stones. If the stones were too heavy, the flax would be damaged. If the stones were too light, the flax would be able to rise up out of the water. This was considered an unpleasant job as the famers would be working with rotten material. The water couldn’t be let out into the river too quickly as it was poisonous to fish.

The flax remained in the dam between 7–14 days. It was a skill to know when to take it out. This was all dependant on the type of flax, the water temperature and the quality of the water. The flax was lifted out and set on the side of the dam to get rid of excess water before returning to the grass field to dry out. The drying process would take about 6 days, although this was dependent on the weather conditions. In some houses, the space in the rafters would be used for drying.

Scutching & Hackling

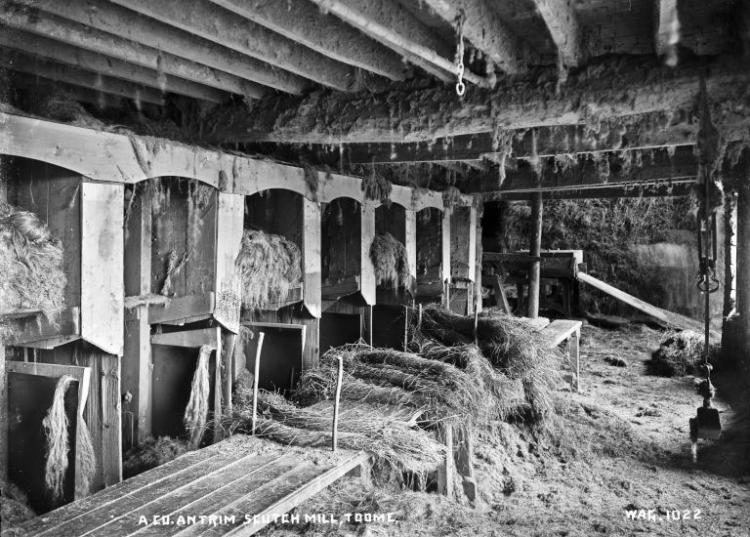

After the flax was dry, before the building of scutch mills, it was broken over the stone to loosen the outside of the flax.

The flax was then scutched to separate the fibres – a process that involves beating the flax straw and removing the woody parts. The flax was then hackled – a process which consists of flax fibres being straightened and sorted into coarse, medium and fine strands.

Hackling was a very skilled job and was where you made your money. A skilled hackler could get the majority of the very fine fibres out on their own and separate them out from the coarse. In the 1800s, most of the flax in Ulster was being scutched in scutch mills. It was quite a slow process but was a lot faster than hand scutching.

Flax would then be boiled in a pot to clean it and then spun on a spinning wheel. One of the reasons Ulster did so well in the linen industry was the high-quality control cloth. The Linen Board would guarantee the quality of Irish linen because there were a lot of linen inspectors working with magnifying glasses to count the number of threads to the inch.

Bleachers Industrialisation

The linen produced in the home was brown linen.

This was sold on to drapers who had the capital and knowledge to bleach the cloth white. Slowly they took over the industry. First by supplying thread from the new factories to the weavers in exchange for the linen produced at a set price. Then by employing weavers directly hand weaving in sheds. Finally by buying steam looms and taking the weaver out of the process.

Emigration

Linen production started off as a cottage industry with the family home being the site of spinning and weaving. A family could get a decent income from these activities combined with a little farming on a small plot of land. Prices of finished cloth could go up and down. One of the things that stimulated emigration from Ulster was downturns in the linen trade, coupled with downturns in agriculture.

The weavers got used to a certain standard of living and when the linen price went down, they immigrated usually to America. The cottage linen weavers created wealth for themselves – even a poor family could afford a spinning wheel, but spinning was the first thing to become industrialised. By the 1820s, industrial spun yarn became available, but it was poor quality. The quality improved and by the 1830s, it wasn’t worth competing against. This reduced family incomes. At the same time linen was facing competition from cotton. Cheaper cotton forced the price of linen down. Many weaving families suffered during the famine. The little money that they had coming into the home was not able to pay for the food which had massively went up in price with the lack of potatoes due to the blight. Some were forced to emigrate while others died of starvation.

After the Great Famine the population was much reduced. Wages started to go up. At the same time steam looms started to be set up in big factories. The linen cottage industry was over. Soon nearly all linen was produced in big factories.

The Great Famine also reduced the number of agricultural labourers. This lead to reduced flax quality. This along with cheaper flax coming in from abroad meant that less and less flax was grown locally. After the First World War hardly any was grown. The Second World War saw subsidies given to farmers to grown flax. Production went up and old scutch mills in Ulster were brought back to life. The subsidies were stopped in the early 1950s and flax disappeared as a crop in the Ulster countryside. Irish linen continued to be produced in the factories in and around Belfast. By the 1970s fashions had permanently changed. Cotton was very cheap, synthetic fibres were even cheaper, linen could not compete. Now very little linen is produced in Ireland.

You Might Also Like

The Mellon Migration Story

Learn more about the story of Thomas Mellon and migration

The McBrien Postcard Collection

Join Fiona McClean, Curatorial Assistant, in exploring the McBrien postcard collection - 'the instant messages of the time'.

Making Mrs Mellon

Our Visitor Guide, Pamela Gunn, has interpreted Mrs Mellon for multiple years. Join us on International Women's Day as we explore her story.